| Homepage Ralph Häussler |

|

- Home

- CV

- Research

-

Celtic Religions

-

Wolf

-

City of Worms

-

Railways

- RailHeritage >

- Aberyswyth-Carmarthen

- RailWorms >

-

Tramways

>

- Tram Amsterdam

- Tram Barcelona

- Tram Basel

- Tram Berlin

- Tram Blackpool

- Tram Bonn

- Tram Bruxelles

- Crich Tram Museum

- Tram Darmstadt

- Tram Dresden

- Tram Edinburgh

- Tram Frankfurt

- Tram Graz

- Tram Grenoble

- Tram Heidelberg

- Tram Innsbruck SLB

- Tram Karlsruhe

- Tram Linz

- Tram Lisboa

- Tram Llandudno (Gt Orme)

- Tram London

- Tram Lyon

- Tram MaLu

- Tram Manchester

- Tram Milano

- Tram Montpellier

- Tram Mulhouse

- Tram Nottingham

- Tram OEG

- Tram Orleans

- Tram Paris

- Tram Reims

- Tram Roma

- Tram Salzburg

- Tram Torino

- Tram Strasbourg

- Tram Wien

- Tram Wien Badner Bahn

- Tram Worms

- Tram Zaragoza

- Tram Zurich

- NarrowGauge >

- Trolleybuses

- U-Bahn Metro

- Epona

- Pets

see below for disclaimer and copyright

Wolf & Mythologie 1 // Wolf & Mythology 1

|

|

Work in progress... For comments, additions, suggestions, etc., please contact me: [email protected]

I tried to indicate copyright for as many images as possible; sorry if I forgot to mention any copyright holder. |

Still today, many people associate wolves with the "bad evil wolf" of fairy tales, like the "Little Red Riding Hood". For the past centuries, wolves were systematically demonised, especially in Europe and North America.

It is important to change people's underlying attitudes if we want to protect wolves in our modern world. And since early childhood, people are being shaped by fairy-tales and werewolf movies. The aim of this page is to show the positive image that wolves once had, and still have today, in many cultures, and the important role wolves play(ed) in mythology and religion in various cultures across time and space: from wolves as divine messengers, to the role of wolves in creation myths and even to "wolf gods" that were (and still are) worshipped. Once, when people lived closer to nature, they observed and respected wolves. Wolves were also important as teachers for humanity, telling people how to live as a family, how to hunt and survive, as in this North American quote: "The wolves followed a path of harmony, and they did not like anything to upset their way." "Wolf was chosen by the Great One to teach the human people how to live in harmony in their families. Wolf was to teach a truth, as each animal... would do also for the humans to survive" (more info). But with increasing urbanisation and exploitation of resources, wolves were more and more given the part of the 'evil' predator who was competing with humans. (please see below for English version) Wie hier in Nordamerika wurden Wölfe von vielen Völkern, Kulturen und Religionen nicht nur für ihre Stärke und Ausdauer, sondern auch für Ihr Familienbewußtsein verehrt. Vielmehr, viele Mythen berichen von der Rolle des Wolfes in Schöpfungsmythen, und wir sehen die göttliche Verehrung des Wolfes in vielen Religionen. Dennoch dominieren bei vielen Menschen heute immer noch negative Mythen über Wölfe, wie die klassischen Märchen vom Rotkäppchen oder vom Wolf und den Sieben Geislein, oder gar von Werwölfen... |

Auch für viele Wissenschaftler ist der Wolf immer noch "der böse Wolf", und so werden auch oft antike Kulte und Mythen anderer Kulturen interpretiert. Das Wort werwolf ist zum ersten Mal von Burchard, Bischof von Worms 1000-1025 belegt. Doch die meisten dieser Geschichten stammen aus einer Zeit, in der Wölfe verteufelt wurden, insbes. durch die Kirche und verstärkt seit dem 16. Jahrhundert. Wachsende Bevölkerungszahlen und Tollwut spielen dabei sicherlich ebenso eine Rolle, wie die Verteufelung durch die Kirche (z.B. der Wolf als Gegenspieler zum Agnus Dei, dem "Lamm Gottes" und damit der christl. Gemeinde), parallel zu den zahlreichen Hexenverbrennungen! Und im 19. Jh. folgte dann die Industrialisierung, ohne Respekt vor Natur, Tieren oder Menschen. In anderen Worten, dies war eine Zeit, in der die Menschen nicht mehr versuchten, mit der Natur zusammenzuleben, sondern sie nur noch aus Profitgier auszubeuten. Dabei haben Menschen Jahrhunderte lang mit Wölfen zusammengelebt und sogar von Wölfen profitiert. Landwirte haben in vielen Teilen der Welt Wölfe verehrt, weil diese Wildschweine und Rotwild von den Äckern vertrieben. Auch in Deutschland dürfen wir nicht vergessen, daß man Wölfe ursprünglich nicht demonisiert hatte. Noch heute sehen wir, wie viele unserer Personennamen den Bestandteil "Wolf" haben (z.B. Wolfgang = "path of the wolf"; Wolfram = "Wolf Raven"; Ralph from Germanic Radulf or Old Norse Ráðúlfr, meaning "Wise Wolf","Counsel Wolf"; Rolf from Ahd. Hrodwulf, "Famous Wolf"; Ulbrecht consists of wulf "wolf" & beraht "bright", i.e. "Bright Wolf"; Ulrica from Middle English Ulric, "Wolf Power", and many more - we find similar wolf names in other languages). And of course, we also find place names, like "Wolfsburg"! Nicht aus Angst vor Wölfen, sondern aus Respekt und Verehrung!

|

Below you find among others the following sections:

|

Im Folgenden finden sich unter anderem diese Sektionen:

|

Wolves in ancient Rome // Wölfe im antiken Rom // Les loups à Rome

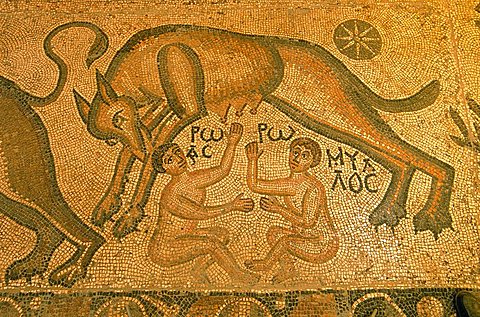

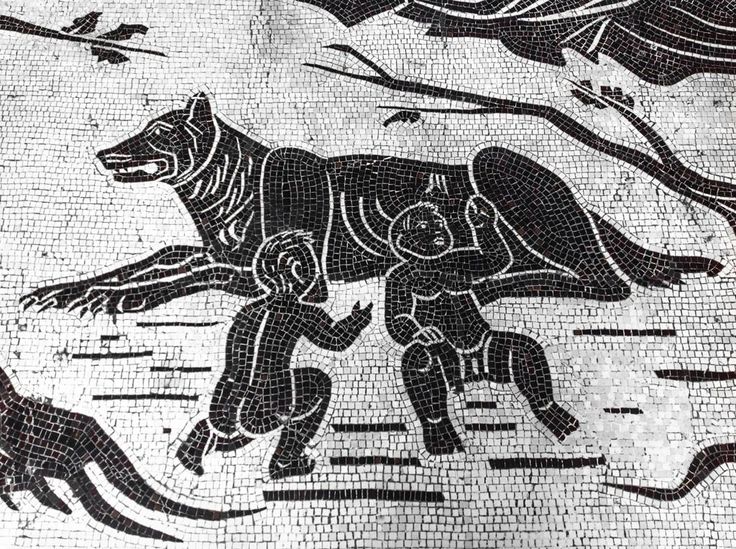

Wolves play a particular role in Roman myth. After all, the mythical founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, were rescued by a she-wolf. According to the myth, Amulius, the king of Alba Longa, had ordered the twins' death by throwing them into the Tiber River. The river god, Tiber, calmed the river and their basket was caught in the roots of a fig tree at the base of the Palatine Hill, where Rome would be founded. The twins were first discovered by a she-wolf, lupa, who suckled them: this famous myth is depicted in countless pieces of Roman art from across the Roman empire (also see images at the bottom of the page). Subsequently, a shepherd and his wife, Faustulus and Acca Larentia, discovered and adopted them (cf. overview by A. Bendlin, "Romulus" in Brill's New Pauly).

Throughout the Roman period, the wolf symbolised Roman power; hence he (or rather, she) appears frequently in art and on Roman coinage, both in the Republic and the Empire (see some of the examples below). The earliest attested statue of the she-wolf suckling the twins was set up by Gnaeus and Quintus Ogulnius, presumably near the Lupercal in 296 BC (Livy 10.23.11-12; Roman Rep. Coinage, p.137, no. 20: 269/266 BC) (this date is very late compared to Etruscan representations of the she-wolf, see images below, and may suggest that the original story is Etruscan in origin). Moreover, we find dedications to the she-wolf, for example from the Roman provinces, like a dedication to the 'Roman she-wolf', Lupa Romana (from Baetica, CIL II.7 139 = ILS 6913), and to the 'august She-Wolf', Lupa Augusta (from Hispania Citerior, CIL II 4603, add. p. 987, 1045 = IRC-1, 132), both of them set up by priests of the 'imperial cult' (seviri), showing the close link between the she-wolf and the Roman state and perhaps local religious understandings regarding the wolf, as we can see, for example, in the religious representations of wolves in pre-Roman Iberia (see below). Mars & the Wolf: The wolf was not only associated with Rome's ancestors, it was also Mars' sacred animal (comparable with the Greek Apollo). After all, Romulus and Remus's mother was Rhea Silvia, forced to become a vestal virgin, and, according to legend, seduced and/or raped by the god Mars. This may explain why a she-wolf came to the rescue of the twins! (This is just like the stories of Apollo sending in wolves in Arcadia and Argos - see right column on this page.)

In our ancient sources, we find a number of indications that directly relate Mars and the wolves. For example, Livy tells us of a "statue of Mars on the Appian Way and the images of the wolves" (Livy 22.1.12). And in Vergil (Aen. 9.566) the epithet Martius is used for the wolf, and Horace (Carm. 1.17.9) talks about Martialis lupos. Livy also reports this well known story where a wolf was again considered as the divine messenger of god Mars: in the 3rd century BC, Romans and Gauls were facing each other for battle when "a hind, pursued by a wolf that had chased it down from the mountains, fled across the plain and ran between the two lines; they then turned in opposite directions, (...) the wolf towards the Romans. For the wolf a passage was opened between the ranks, but the hind was killed by the Gauls." This was considered a good omen: "the Roman side called out: 'that way flight and slaughter have shaped their course, where you see the beast lie slain that is sacred to Diana; on this side the wolf, sacred to Mars, unhurt and sound, has reminded us of the Martian race and of our Founder'" (10.27). The wolf is a divine messenger that relates to Mars and to Romulus, Rome's founder.

Silver denarius from Rome (45 BC), with the goddess Juno Sospita (the "Saviour", protectress of Rome) wearing goat skin headdress. Rv.: Two Roman symbols: the she-wolf and Jupiter's eagle. The she-wolf places stick on fire and an eagle is fanning the flames (Are they responsibe for keeping the hearth of the state, in the temple of Vesta, burning? Commemorating Caesar's renovation of Juno Sospita's temple?) (Crawford 472/1).

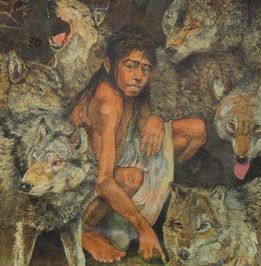

Wolf Children - Wolfskinder - Enfants loups

Romulus and Remus might just be a fantastic story to demonstrate the divine intervention of Rome's founder(s). But across the ages, we find similar stories of children being raised by wolves in many cultures across the globe:

In ancient Crete, for example, we find the mythical story of Miletus. In Antoninus Liberalis' Metamorphoses (30), we are told: "In Crete, Apollo and Acallis, daughter of Minos, had a child called Miletus. Fearing Minos, Acallis exposed him in the wood. By the will of Apollo, wolves would turn up to guard him and to give milk in turn. Then herdsmen came across him and gathered him and brought him up in their huts" (Translation: Francis Celoria, The Metamorphoses...). Again, we see the role of Apollo, the "wolf-born god" in this myth, with wolves as his messengers and/or divine animals (also see e.g. story of Argos on this page). And in Irish mythology, for example, we find king Cormac Mac Airt who was adopted and reared by a she-wolf with her cubs in the caves of Keash (County Sligo). Of course, we should not ignore the more recent stories of "feral children", raised by wolves, like the famous (and dubious) case of Kamala and Amala in the 1920's (see Singh and Zingg, Wolf-Children and Feral Man, 1942 and one of the critical reviews) - probably a story as unbelievable as Rudyard Kipling's Mowgli in his Jungle Book from 1894. But perhaps not? After all, there seem to be countless stories of this kind across time and space! - Can they be all a hoax...? Lupercalia in Rome // Die Lupercalia, das römische Fest der Wölfe(?)

The she-wolf and the twins in the Lupercal. Marble base, Forum Boarium, Rome (Museo della Civilta Romana, Rome) The she-wolf and the twins in the Lupercal. Marble base, Forum Boarium, Rome (Museo della Civilta Romana, Rome)

In Rome, we also find a religious 'wolf' festival, the Lupercalia, and a prieshood, the Luperci, that are seemingly named after the wolf, 'lupus'. It was a fertility festival with rather strange rites, like a wild chase, that took place annually on the 15th February, starting at the Lupercal on the Palatin (the presumed place where Romulus and Remus were suckled by the she-wolf); there are also some parallels with the Lykaia that was celebrated in Arcadia (see right column). Indeed, Livy wrote, in the Augustan period, about "the festival of the Lupercalia (...). Evander, an Arcadian, had held that territory [i.e. of Rome] many ages before, and had introduced an annual festival from Arcadia in which young men ran about naked for sport and wantonness, in honour of the Lycaean Pan, whom the Romans afterwards called Inuus." (Livy 1.5, also cf. Plut. Caes. 61).

Also in his Romulus, Plutarch writes: "The name of the festival has the meaning of the Greek ‘Lycaea,’ or feast of wolves, which makes it seem of great antiquity and derived from the Arcadians in the following of Evander. [4] Indeed, this meaning of the name is commonly accepted; for it can be connected with the she-wolf of story. And besides, we see that the Luperci begin their course around the city at that point where Romulus is said to have been exposed." (Plut. Rom. 21), and he continues that "Romulus and Remus, after their victory over Amulius, ran exultantly to the spot where, when they were babes, the she-wolf gave them suck, and that the festival is conducted in imitation of this action." The comparison with Arcadian Lykaia is likely to be an explanatory myth created during the Republic when people thought about the origin of the Lupercalia. The ritual itself has lots of similarities with typical rites of passage and might have been an archaic ritual of an agricultural community, similar to other cultures. Among others, we are told that "many of the noble youths and of the magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs" (Plutarch Caesar 61). The Lupercalia was such an important festival for Rome and Roman identity that it continued well into late Antiquity despite progressive Christianisation (cf. D. Baudy, "Lupercalia", Brill's New Pauly). And although the Lupercalia might have taken place for more than 1,000 years, knowledge of the festival's meaning was already lost in the late Republic, and various ancient authors are already speculating about the meaning of the festival and its rituals. Around AD100, Plutarch, in his "Roman questions" (Plut. Quaes. Rom. 68), asks this: "Why do the Luperci sacrifice a dog? The Luperci are men who race through the city on the Lupercalia, lightly clad in loin-cloths, striking those whom they meet with a strip of leather. (...) Or is it that lupus means ‘wolf’ and the Lupercalia is the Wolf Festival, and that the dog is hostile to the wolf, and for this reason is sacrificed at the Wolf Festival? Or is it that the dogs bark at the Luperci and annoy them as they race about in the city? Or is it that the sacrifice is made to Pan, and a dog is something dear to Pan because of his herds of goats?" (In his Caesar 61, Plutarch also suggests that a dog was sacrificed because it is a purification ritual, and puppies were also used in Greek ritual). Wolves & Shamanism

This section is still very incomplete. - More as soon as I find the time.

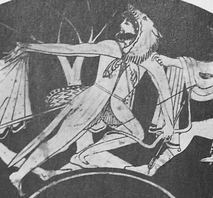

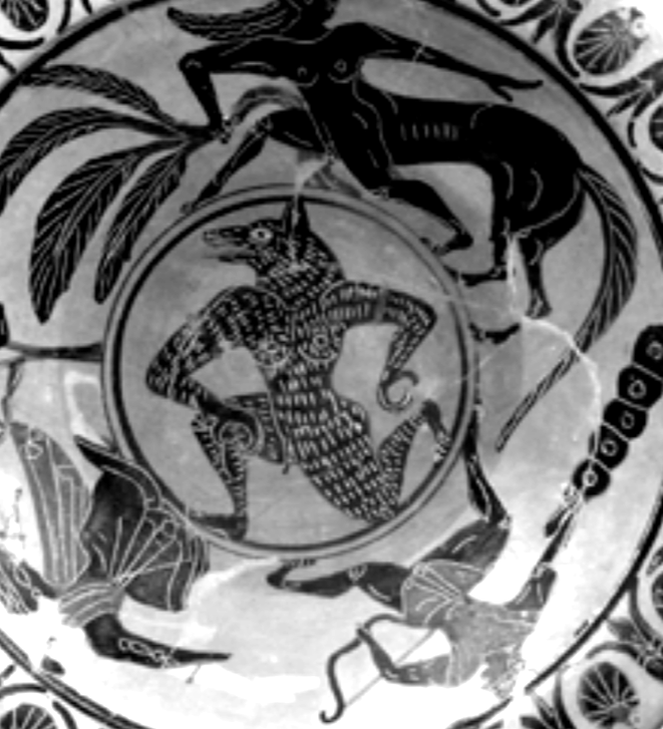

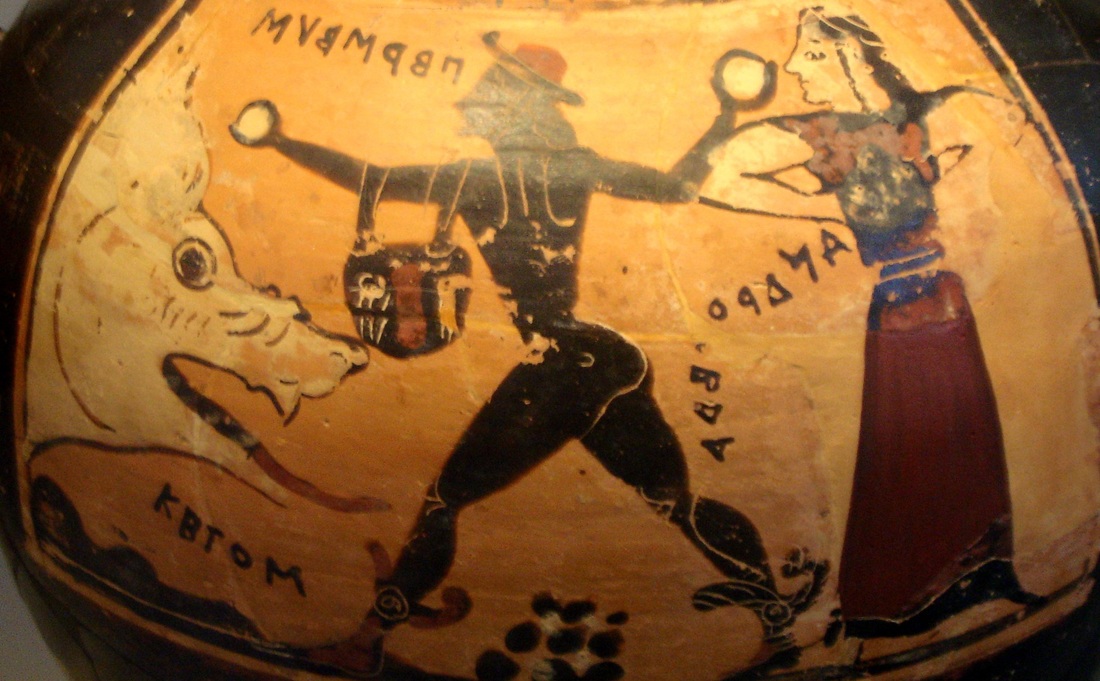

We already have seen that people seem to (have) dress(ed) up as wolves during religious ceremonies, for example in the case of the Tlingit (see next page). There is more evidence for this ritual from various cultures. For example, the Navajo word for wolf, "mai-coh," also means witch: a person could transform if he or she wore a wolf skin. This is also something we see in this 2,500-year old Greek vase painting: a person wearing a wolf skin; was this Dolon, a hero that first appears in the Illiad (in the so-called Doloneia [Book 10], probably a later addition to Homer's Illiad; cf. J. Latacz, "Doloneia." New Pauly): Hector 'clad him in the skin of a grey wolf, and on his head he set a cap of ferret skin' (Hom. Il. 10.332-335; also Hom. Il. 10.454). Story and vase paintings might provide an insight into some rituals of pre-Homeric, Homeric or Archaic times. Dressing up with a wolf-skin or hat can be seen in many cultures, and Dolon's story might be a reflection of earlier religious / shamanistic understandings. Wolves in Nordic/Germanic Myths // Wölfe in nordischen & germanischen Mythen

In Norse mythology, we find numerous wolves. There are the wolves Geri and Freki, accompanying god Odin. Skalli/Sköll and Hati are responsible for chasing the sun and moon across the heavens, and finally devouring them at Ragnarök when the world comes to an end (in another source, it is the wolf Fenrir).

This "chasing of the sun/moon" is essential for Norse cosmology. It is an etiological myth that tries to explain the movement of sun and moon; the wolves Skalli and Hati, like their counterparts in other myths, are responsible for the movement of sun and moon; without them, day and night would not exist, and consequently they are create the cycles of the seasons. It shows the role of wolves in cosmology. A similar role can be found in Chinese mythology where Tiangou, 天狗 (meaning 'heavenly dog'), equally chases the sun, and is thought to devour it during an eclipse (hence, according to one myth, Tiangou is chased away by arrow by his arch enemy, Zhang Xian, 張仙 - see image below) (also cf. Celtic mythology, below); interestingly some Greek writers wrote that the Greek word for the "year", λυκάβας, was derived from λύκος “wolf” and βαίνω “to walk”, like the role of Skalli and Tiangou in chasing the son, walking over the sky/heavens... (cf. Ael. Nat. Anim. 10.26; Artemidorus, Onirocrit. 2.12; Eustathius on Hom. Od. 14.161, p. 1756). In Norse myth, there is also Skalli's and Hati's father, the wolf Fenrir (or, Fenrisúlfr, Hróðvitnir - Old Norse for "fen-dweller", "Fenris wolf" and "Fame-Wolf" respectively). Fenris is the son of god Loki and destined to kill god Odin. Here, one might also want to refer to the famous Anglo-Saxon epos, Beowulf. Different etymolgoies have been suggested, but it seems certain that the -wulf does mean 'wolf'. One interpretation of Beowolf is Þórólfr ("Thor Wolf"), perhaps the wolf of the Germanic god Thor or Beow; or perhaps as beado-wulf, i.e. "battle/war wolf", similar to Icelandic Bodulfr "war wolf" (cf. Anglo-Saxon Dictionnary; Shippey, Beowulf). Langobards: Wolf as guide & divine messenger

Just a short note on the Lombards or Langobards, a Germanic people that had invaded Italy in the 6th century AD and created the Lombard Kingdom. In the 8th-century History of the Lombards, the Historia Langobardorum (IV.37), we are told that Leupchis had five sons, who, still children, were abducted by the Avars who had invaded the Duchy of Friuli (approximately AD 610); one of them, Lopichis, managed to escape and after a long odyssey return to Italy. On his way, he met a wolf who became his companion and guide: ei lupus adveniens comes itineris et ductor effectus est. As suggested by Carlo Donà (2003, 239-40), Lopichis still lived in a world full of 'pagan echoes': the wolf, "sibi .... divinitus datum esse", may well have been a divine messanger, perhaps of god Wotan.

As so often, also in Irish and Welsh mythology, written down in the Middle Ages, our texts were compiled by Christian/Catholic monks, hence they provide us with a re-telling of stories from a Christian viewpoint. Apart from serious misunderstandings and inaccuracies, this may imply deliberate or unconscious misrepresentations of 'pagan' understandings, knowledge of which might have got significantly lost by the time of writing. As we have seen earlier, wolves played various roles in Germanic/Norse mythology, and the pre-Christian Lombard "pantheon" might have been similar; we have seen wolves accompanying god Odin, for example, and the wolf as guide might reflect this role in Germanic/Lombard myth; in Christian texts, one favoured the Lamb [Agnus Dei], and wolves were automatically given the role of the evil spirit...). (Cf. W. Haubrichs, 'Die "Erzählung des Helden" in narrativen Passagen der Historia Langobardorum', in V. Millet and H. Sahm (eds), Narration and Hero, 2014, p. 295, for a quote of the passage and a disucssion on the role of the wolf, cf. Carlo Donà, Per le vie dell'altro mondo: l'animale guida e il mito del viaggo. 2003, p.239). Wolf in Celtic Mythology, ancient and medieval // Der Wolf in der keltischen Mythologie // Le loup dans la mythologie celtique

For the 'Celts', we need to distinguish different regions of the Celtic World and different periods, notably between the Continental 'Celts' and the Insular 'Celts'.

In medieval Celtic mythology (i.e. mainly Wales and Ireland), where ancient myths and legends were written down in a Christianising context, wolves play a number of important roles. Similar to the Roman story of Romulus and Remus, a future king was once again reared by a she-wolf: Cormac mac Airt grew up to become an important High King of Ireland (v. supra). In many Irish/Welsh myths, the wolf is usually a helper and a guide. We also find myths of deities in wolf form, like the goddess Morrigana appearing in wolf form, but was defeated by the hero Cú Chulainn (cf. The Táin). There is also the old Gaelic/Irish month faoilleach, which comes from faol or faol-chù, "wolf", i.e. the "Month of the Wolf", February (in other cultures, January). The pre-medieval 'Celtic World' is of course much larger, covering most of Europe for over one millennium, from the Hallstatt period down to late Antiquity. It is therefore no surprise that wolves probably played a different role in each local myth and local religion, though there might be some common denominator. Since religious affairs were not written down in ancient times (according to Caesar, the druids did not allow this!), our knowledge of ancient Celtic mythology is largely based on iconographic representations in art and on coinage. We are really dealing with a jigsaw puzzle where most of the pieces are lost. Various objects provide important clues. For example, the wolf does appear on a number of coins in the Iron Age, for example among the Carnutes, but it is difficult to explain his mythical, religious role. See the coins below with a variety of wolf depictions. Romano-British Wolves:

Apollo Cunomaglus, Cunobelinus,... The words "dog" and "wolf" are often interchangeable in many cultures (e.g. inu and ookami in Japanese). This is also the case in ancient Celtic, even more so: the word cuno can mean both dog and wolf (see Delamarre, Dictionnaire de langue gauloise, 2003, pp.131-132, s.v. cuno- 'chien', 'loup'). In the words of Delamarre: "Le nom du chien a servi en celtique, par métaphore, ou par tabou, a designer le loup." (Also in ancient Irish, cú; the Indo-European word similar to lupus & lykos crops up rarely in Celtic texts, but see for example Ulkos on Lepontic monetary legends in ancient north Italy). Consequently, the Britanno-Celtic name Cunomaglus, is interesting for us. Rather than "Hound Lord", as has often been suggested, we can follow the translation of the etymologist Xavier Delamarre and translate Cunomaglus with "Wolf Lord" (Delamarre, loc.cit., "Seigneur-Loup"). Moreover, Cunomaglus is used as an epithet for a local Romano-Celtic/British god that was called Apollo on Latin inscriptions, for example at Nettleton Shrub (Wiltshire) in Roman Britain where we find this dedication by a woman who also has a Celtic name and might therefore worship an 'indigenous' (Celtic, British) god:

There are many Celtic personal names that consist of the word cuno "wolf". For example: Cunobelinus "Strong-Wolf" (a pre-Roman British king), Cunomapatis "Wolf-Child", Ianuconius "Just-Wolf", and many more. Like in other cultures, we also find wolf names for ethnic groups / peoples and for place names (see Delamarre, loc.cit.). The personal name Cunobelinus is particularly interesting since the component Belinus is also the name for an important Celtic god, Belinus/Belenos, who, in the Roman period, was equally equated with Apollo (well known from Aquileia). Belenus was first attested in Southern Gaul, but in Roman times, Sucellos/Silvanus seems to have taken his place, like on this figurine from Vienne where the god Sucellos wears a wolf skin (Just coincidence? On many Sucellos representations, he does not wear a wolf skin. For Sucellos, also see next section). There are a number of wolf- or dog-like animals depicted on the famous Gundestrup Cauldron (Copenhagen Museum), roughly dating to the 1st century BC. It is widely assumed that it shows 'Celtic' myths. But our interpretations of the numerous panels vary widely! And therefore our understanding of the role of wolves/dogs is equally problematic. For some people, the wolf accompanies the (heroic) dead into the Otherworld, and some scholars are quick to make associations with Odin's wolf in Germanic mythology and even the Greek three-headed dog, Cerberus (as for example H. Eilenstein, Ursprünge der keltischen Mythologie, p.202).

Yes, there might well be a link to the Otherworld, or to life after death, but the wolf might also represent, for example, longevity. Moreover, the wolf also appears in other situations, for example accompanying deities, like some kind of "Cernunnos (pre-Shiva)", master of animals, on the panel below. This also leads us to an important South Gaulish deity, Sucellos, the "mallet god", sometimes wearing a wolf-skin and usually accompanied by what seems to be a dog (in the 1st-3rd century AD, when adopting the image of the Roman god Silvanus to represent their native deity, the Gauls also adopted the dog as the god's companion from Roman iconography; was it meant to symbolise a wolf?). Again, Sucellos is a chthonic god, like most deities (we also should not forget that, for example, mother goddesses are equally 'chthonic' in nature). And although this might have been the deity that Caesar interpreted as Dispater, Sucellos is more than just a god of the underworld; he can also be a healing deity (e.g. at Glanum, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence). We see wolves closely associated with a powerful Celtic (or Gallo-Roman) god. Unfortunately, as is common in Antiquity, all these pieces of evidence are still not sufficient to create a precise understanding of the associated myths and religious significance. Although a certain image of wolf and deity/deities emerges in the Celtic world, we are still far away from really understanding what is happening here. Curchin, in his Romanization of Central Spain, also reminds of other pieces of evidence: like Appian (Iberica 48) mentioning a Celtiberian herald who wears a wolf-skin; and Francisco Marco Simón (1991: 96) discusses vases from Numantia wearing wolf skins. Paralells with Sucellos are perhaps less likely, but the wearing of wolf skins obviously had "magical" roles in numerous cultures. There is a lot of literature on 'Celtic' myth and religion, but wolves are rarely discussed. But see for example Miranda Aldhouse-Green, An Archaeology of Images: Iconology and Cosmology in Iron Age and Roman Europe.

Iberian and Celtiberian wolf myths // Iberische Wolfsmythen

A little excursion to the Iberian peninsula where we find populations that are categorised as Celts, Iberians and Celtiberians:

Further Reading on Iberia: for example, Héctor Uroz Rodríguez, Practicas rituales, iconografía vascular y cultura material...

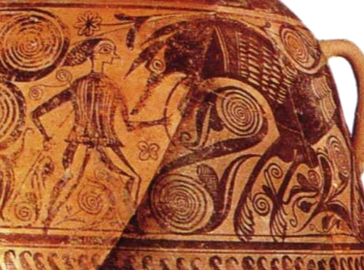

Jorge García Cardiel ('El combate contre el mal', Complutum 25(1), 2014: 159-175) interprets the "wolf" as evil in Iberian iconography. But was this really the case? We really need to scrutinise the evidence for this. In the image of the wolf and the boy, below, are we really dealing with an image of an aristocrat fighting a mythical beast, in form of a wolf, presenting evil (cf. Cardiel 2014)? Or are modern scholars not influenced by their own cultural background, like the demonisation of the wolf in Christianity and in the last centuries in western Europe. Indeed, we may ask whether we may not be dealing with something quite different? After all, this comes from a period with relatively few proto-urban and urban settlements and a basically agricultural society. Once again, the wolf is likely to symbolise the perfect 'warrior', the instinctive forces of nature, symbolising 'the survival of the fittest'. The wolf is a guide, both in this life and in the afterlife. On the vase painting below we see the boy, the young/future warrior, standing face-to-face with a larger-than-life wolf. This does not represent a fight, especially when we consider the decoration of the entire vessell. Perhaps it shows a rite de passage (or coming-to-age ritual), as we have seen in so many other cultures (see e.g., José Carolos Fernandéz). We also should not forget the wolf's role as teacher, here perhaps for good hunting. Celtic Ireland

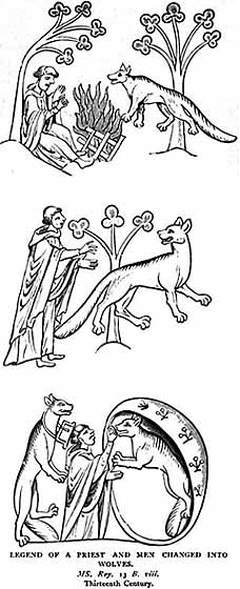

Celtic Ireland: Let's go back to Medieval Ireland. In Geralde de Barri's Topographia Hibernica (MS. Roy 13B.viii) from the 13th century AD), we find a story that has some resemblance to wolf myths in other cultures: humans turning to wolves for a certain period as well as wolves showing travellers the right way.

The story tells of a priest travelling from Ulster to Meath in AD1182 who met a talking wolf. He told the priest that he came from Ossory (kingdom / diocese around Kilkenny), "on whose race lay an ancient curse whereby every seven years a man and a woman were transformed into wolves; at the end of seven years they recovered their proper form, and two other suffered a like transformation. He and his wife were the present victims of the course; his wife was at the point of death, and he prayed the priest to come and give her the viaticum' (i.e. the last rites / Holy Eucharist). The priest did it and the grateful wolf showed the priest the right road to Meath (cf. J.R. Green, Short history of the English People, II, London 1908, lxix-lxxx). |

Wolves in Greek Myth // Wölfe in griechischen Mythen // Les loups dans la mythologie grecque

The wolf play an important role in Greek religions. But his/her role varies enormously. The wolf is often related to the Greek gods Zeus, Apollo, Artemis and Leto, as we shall see below. Wolves seem to act as divine messengers of the gods, notably of Apollo. A particularly well attested wolf cult can be found in the more remote, mountainous region of Arcadia, on the Peloponnese, notably around the Mount Lykaion, the alleged birthplace of Zeus (for which cf. e.g. Mt Lykaion Survey Project; click here for overview), from which we also get the earliest 'werewolf' stories. Here and elsewhere, we need to piece together the ancient evidence for this wolf cult.

King Lycaon - Before we discuss 'wolf deities', let us focus on the ancient stories of humans being transformed into a wolf, most of which relate to Arcadia and seem to relate directly to the worship of a god called Zeus Lykaios, 'Wolf-Zeus'. The story of King Lykaon's transformation into a wolf might therefore just be an explanatory myth to explain the 'wolf cult' in Arcadia; there might also be other symbolic meanings attached to this myth. At the same time, we have to bear in mind that these stories were not written by Arcadians, but by outsiders who lived in cities, like Athens and Rome, and therefore quite detached from nature and also having a certain agenda for mentioning these stories (most notably in Plato - see below). First, we have to remember that these early myths do not relate to "werewolves"; the term itself did not exist: Greeks usually just used the word 'wolf', lykos (but see Latin versipellis below). Also, the typical medieval and modern 'werewolf' attributes, like the full moon, are usually missing in Antiquity. In the case of the famous story of King Lykaon, we can see that we are dealing with divine punishment by Zeus who was betrayed by king Lykaon, not some 'werewolf curse'. Moreover, Lykaon stayed a wolf! (For the various accounts cf. e.g. Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.209-243; Plato, Republic VIII, 16, 565d-566a; Hyginus, Scholiast on Caes. Germ.). Ovid, writing around A.D. 8, provides a rather colourful depiction of Lykaon's transformation: "His clothes became bristling hair, his arms became legs. He was a wolf, but kept some vestige of his former shape. There were the same grey hairs, the same violent face, the same glittering eyes, the same savage image." Already 400 years earlier, Plato provided the earliest mentioning of a myth relating to Zeus Lykaios: in his Republic we are told of "the legend that is told of the shrine of Lycaean Zeus in Arcadia (...) The story goes that he who tastes of the one bit of human entrails minced up with those of other victims is inevitably transformed into a wolf.” (Rep. 565d-e). This is important to understand some of the sacrifices and rituals that took place in honour of Zeus Lykaios in Arcardia (for Plato, of course, the story was only mentioned in passing, as a metaphor for contemporay politics, i.e. the tyrant turning into a "man-eating wolf"). Tasting human flesh is a recurrent theme in the cult of Zeus Lykaios. We also should not forget that there are many accounts of King Lykaon. And in many stories a transformation was not mentioned at all (e.g., Clement of Alexandria, Nonnus, Eratosthenes, Arnobius). Instead Lykaon is even said to 'maintain his father's institutions in righteousness', and it was his sons who upset Zeus: 'they sacrificed a child and mixed his flesh with that of the victim'; in return Zeus killed the murderers (cf. Nicolaus Damascenus, Frag. 43 (Fr. Hist.Graec. 3.378; Suidas, s.v. Λυκάων). Wolf worship in Arcadia In any case, ancient Arcadia certainly seems to be have been an important centre of wolf worship. The story of king Lykaon leads us to Zeus Lykaios (another Arcadian "wolf god" was Apollo Lykaios, see below). Zeus Lykaios is the "Wolf Zeus". In his honour, a religious festival called the Lykaia was celebrated on Mount Lykaion, the "wolf mountain" (see overview and 2015-paper of recent excavation by David Romano and Mary Voyatzis, suggesting ritual activities on Mount Lykaison since circa 3,000 BC). Regarding these sacrifices during the Lykaia, we are also having the incredible story of an Olympic boxing champion that Pausanias (6.8.2) tells us: "Damarchus, an Arcadian of Parrhasia, (...) who changed his shape into that of a wolf at the sacrifice to Zeus Lykaios, and how nine years after he became a man again". He allegedly was turned into a wolf after he ate the flesh of a boy that was sacrificed to Zeus Lykaios by the Arcadians; are we dealing with a regular (annual?) event by which one member of the community was cast out (or sacrificed?) as a wolf. Pausanias, writing in the Roman period, tell us that he "cannot believe what the romancers say about him [i.e. Damarchus]". But several accounts of this story have survived; in other accounts Damarchus' name was Demaenetus, like here in Pliny's Natural History (NH 8.34): "Agriopas (...) informs us that Demænetus, the Parrhasian, during a sacrifice of human victims, which the Arcadians were offering up to the Lycæan Jupiter, tasted the entrails of a boy who had been slaughtered; upon which he was turned into a wolf, but, ten years afterwards, was restored to his original shape and his calling of an athlete, and returned victorious in the pugilistic contests at the Olympic games." (also cf. Scopas FGrH 413 F 1; Varro in Aug. Civ. 18.17; cf. René Bloch, "Demaenetus", Brill’s New Pauly; N.B.: 10 instead of 9 years here). This story is one of many pieces of evidence for 'wolf worship' and transformation that probably originated in earlier times in the Bronze Age and continued, in one way or another, into later times in this rather remote region of Arcadia, and which authors like Pausanias and Pliny, writing in the Roman period, obviously found rather odd. Later in his work, Pausanias specifically mentions wolf transformation during a sacrifice to Zeus Lykaios: "8.2.6 - All through the ages, many events that have occurred in the past, and even some that occur today, have been generally discredited because of the lies built up on a foundation of fact. It is said, for instance, that ever since the time of Lycaon a man has changed into a wolf at the sacrifice to Lycaean Zeus, but that the change is not for life; if, when he is a wolf, he abstains from human flesh, after nine years he becomes a man again, but if he tastes human flesh he remains a beast for ever." Pausanias' account might suggest a particlar form of ritual by which one man was selected (or rather, cast out) as an annual(?) sacrifice. A complimentary story on the Arcadians was reported by Euanthes according to Pliny the Elder's Natural History from AD79 (FGrHist 320 = Plin. NH 8.34): "Euanthes ... informs us that the Arcadians assert that a member of the family of one Anthus is chosen by lot, and then taken to a certain lake in that district, where, after suspending his clothes on an oak, he swims across the water and goes away into the desert, where he is changed into a wolf and associates with other animals of the same species for a space of nine years. If he has kept himself from beholding a man during the whole of that time, he returns to the same lake, and, after swimming across it, resumes his original form, only with the addition of nine years in age to his former appearance. To this Fabius adds, that he takes his former clothes as well. It is really wonderful to what a length the credulity of the Greeks will go!" (Again, Roman scepticism about Greek myths!) All this seems to suggest a kind of initiation ritual, rite de passage, coming-to-age ritual: a boy (not a man, as in Pausanias' account), selected by lot, going out into the 'dessert', living like a wolf (cf. the kypteia in nearby Sparta or the Lupercalia in Rome). But why? Is this a curse on the local community? Or is the 'wolf', having been cast out of his community, a kind of sacrifice of the community, or a 'scapegoat' - the boy who was cast out for a number of years might be important to guarantee the well-being and suvival of the community. (Cf. e.g., W. Burkert, Homo Necans, p.87; also see below for the 12th-century AD Irish story of a wolf transformation lasting seven years of a man and a woman chosen by lot every seven years.) The story of king Lykaon has been interpreted in various ways: it was considered an etiological myth that explained a 'brotherhood of men-wolves' and the worship of a 'wolf god'. Others, like Burkert (1983:84-93), consider the metamorphosis to be 'equivalent to a symbolic death' during a 'tribal' initiation rite (or rite of passage). We also see certain symbolic contrasts: human vs. animal; civilisation vs. wildness, etc. Lykaon as king and as wolf show the king as 'civiliser' (urbanism, human society, institutions) versus 'wildness', as well as Lykaon's impiety and transgression, resulting in Zeus' punishment: the god might also reject the 'commensality' with men. (Cf. M. Jost, 'The Religious System in Arcadia' in D. Odgen, Companion to Greek Religion, p.275). Apart from the symbolic value, we also should not forget that all these texts somehow seem to refer to some kind of human sacrifice taking place in Arcadia for Zeus. But we also should not forget other possible interpretations of the myth, and we must take into account the nature of our sources: we do not actually have Arcadian sources, but an Athenian philosopher (Plato), a 1st-century AD natural historian from Rome (Pliny the Elder), and a 2nd-century AD geographer from Lydia (Pausanias and his Description of Greece). The Arcadian rituals and myths probably come from much older times: with people living in a rural area, in harmony with nature, their relationship with animals might have been much more positive compared to Plato, Pliny and Pausanias, but unfortunately Arcadian accounts have not survived. The story of wolf transformation spread more widely and seems to have become quite popular during the Roman period. We learn about the entertaining story of Niceros who, during Trimalchios' fantastic dinner party, told this story about his friend, a soldier, who transformed into a wolf in a graveyard: "He stripped himself and put all his clothes by the roadside. My heart was in my mouth, but I stood like a dead man. He made a ring of water round his clothes and suddenly turned into a wolf. Please do not think I am joking; I would not lie about this for any fortune in the world. But as I was saying, after he had turned into a wolf, he began to howl, and ran off into the woods. At first I hardly knew where I was, then I went up to take his clothes; but they had all turned into stone..."; and later he became a human again, returning to Nicoros' house (Petronius, Satyricon, 61f, c.AD60). This story is probably based on the myths from Arcadia, but they now reveal a certain common belief in 'werewolves'. There still is no demonising, no monsterous creature in any of these reports - unlike medieval and modern werewolf accounts - just a normal wolf... Nicoros' friend is described in Latin as a versipellis ('turning grey'), which means a shape-shifter (see the short account on the 'versipellis' in Pliny's Natural History 8.34). Scythia: wolf shape-shifters

Talking about 'shape-shifters', this story is interesting. The 5th-century BC Greek historian Herodotos (4.105) has recorded a story he heard about the Neuri who are said to have lived north of Scythia (roughly northern Ukraine, southern Belarus today): "It may be that these people are wizards; [2] for the Scythians, and the Greeks settled in Scythia, say that once a year every one of the Neuri becomes a wolf for a few days and changes back again to his former shape. Those who tell this tale do not convince me; but they tell it nonetheless, and swear to its truth". But perhaps we need to understand Herodotos' story quite differently: "becoming a wolf for a few days" could be part of an annual ritual, a 'rite de passage', perhaps comparable with NW American Indians (see page 2 of website).

Lycaonia and Lukkawana "Wolf Land"

A Greek silver obol from Lycaonia (probably c.324/3 BC), showing Herakles on the obverse and a wolf and a star on the reverse (with legend: "ΛΑ-ΡΑΝ" and monogram ΠΑΡ). The wolf here symbolised the country. But why? For some, the name has merely similarities with the Greek word for wolf, lykos. On the other hand, already in Hittite times (2nd millenium BC) we learn of the "wolf land", Lukkawana ("lukka" is Hittite for "wolf", similar to Greek lykos and Latin lupos). The association with wolves might therefore be more ancient than some people think...

Apollo Lykaios, Lord of the Wolves (?) // Apollo, der Herr der Wölfe

Another Greek god is Apollo Lykaios, "Apollo Wolf", or "Apollo Lord of the Wolves" (see below). It has been speculated that Apollo's original, pre-anthropomorphic form, was that of a wolf, though this is highly speculative: many Greco-Roman anthropomorphic deities might have had non-human predecessors, but we generally lack sufficient evidence to make such assumptions. It has also been suggested that Apollo Lykaios might here simply refer to the place/location of some the Apollo shrines, or the Lykaios means "bright".

However, our ancient sources clearly associate Apollo with wolves. Already in Homer's epos on the Trojan war (c.850 BC), we hear of a "vow to Apollo, the wolf-born (Λυκηγενής) god, famed for his bow, that he would sacrifice a glorious hecatomb of firstling lambs" (Homer Iliad 4.85). Who is this god Apollo, the son of Zeus and Leto? According to Aelian, in his De Nature Animalium (10.26), Leto had turned herself into a λύκαιναν, a she-wolf. Apollo, and his twin sister, the goddess Artemis, are therefore indeed "wolf-born", as described by Homer. In the 4th-century BC, Aristotle also cites this mythical story: "...when they transported Leto ... from the land of the Hyperboreans to the island of Delos, she assumed the form of a she-wolf to escape the anger of Hera" (Aristot. Hist. an. 58a15f). In another variation, Leto was accompanied by wolves (cf. Ael. NA 10.26) - a story that might be depicted on the image below. Antonius Liberalis (35), reporting a tale from Nicander (2nd century BC) and from Menecrates of Xanthus (4th century BC) in his Lyciaca, also tells us about Leto, but a slightly different account. Having giving birth to Apollo and Artemis, she went to Lycia with her twins where she wanted "to bathe her children" in a spring when some "herdsmen drove her away"; then, "wolves came out to meet her, and wagging their tails, led the way guiding her to the River Xanthus. She drank the water and bathed the babes and consecrated the Xanthus to Apollo while the land which had been called Termillis she renamed Lycia [Wolf Land] from the wolves that had guided her" (Translation: Francis Celoria) (see below for the name Lycia and the Greek word lykos, 'wolf'). The epithet Lykaios/Lyceus shows Apollo as protector and master of wolves (λύκοι). For example, the god Apollo Lykaios was invoked to ward off enemies (Aeschylus, Seven, 145):

"And you, Apollo, lord of the Wolf, be a wolf to the enemy force and give them groan for groan!" And as an averter of evil, he protects herds, flocks and the young. We can see some parallels to the divine/protective role of wolves in other cultures, for example in Japan. According to Pausanias (2.19.3f), the (mythical king) Danaus established a sanctuary in honour of Apollo Lyceus/Lykaios at Argos where the most famous of all Apollo's temples was consecrated to him under the title of “Wolf-god.” (cf. e.g. Weir Smyth, Aeschylus, vol. 2, Cambridge, MA. Harvard U.P. 1926). In the words of Pausanias (2.19, 3-4): "The most famous building in the city of Argos is the sanctuary of Apollo Lycius (Wolf-god). (...) the original temple and wooden image were the offering of Danaus. (...). The reason why Danaus founded a sanctuary of Apollo Lycius was this. On coming to Argos he claimed the kingdom against Gelanor (...). Many plausible arguments were brought forward by both parties (...). At dawn a wolf fell upon a herd of oxen that was pasturing before the wall, and attacked and fought with the bull that was the leader of the herd. It occurred to the Argives that Gelanor was like the bull and Danaus like the wolf, for as the wolf will not live with men, so Danaus up to that time had not lived with them. It was because the wolf overcame the bull that Danaus won the kingdom. Accordingly, believing that Apollo had brought the wolf on the herd, he founded a sanctuary of Apollo Lycius." See below for a silver coin from Argos depicting the wolf sent by god Apollo. Uncertain is the meaning of the goddess Artemis Lykaina (Λύκαινα, "she-wolf"): As with her twin brother Apollo, this epithet might refer to her birth (v.supra)? We also have a spell in Papyri Graecae Magicae (PGM) 3.434-35 in which Artemis was called Lykaina. Around AD270, Porphyry (de abstinentia 4.16) wrote that the Persians called Artemis/Diana a 'she-wolf'.

Electron stater with a wolf-like mythological creature from Cyzicus (Mysia), dating to c.550-500 BC. Some scholars suggested a lion, as in the Persian lion-headed griffins, or even the Mithraic Areimanios, but it looks more like a wolf-headed creature. We are dealing with a local god whose identity remains unknown.

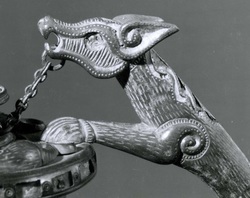

Another Apollo Lykaios? This seems to be a representation of the Apollo statue from Tarsus (Cilicia). Here, Apollo seems to be holding two wolves at their forelegs, one in each hand (c. A.D.235-238; SNG Paris 1590). We also find 5th-century BC obols from Tarsus showing the god Ba'al and the forepart of a wolf (SNG Paris 444 var.). (Also cf. Hittite myth, see left column.)

Apollo's divine messengers: wolves

We also have the story of the town of Lykoreia (Λυκώρεια), a polis on the summit in the Parnassus region (Central Greece, near Delphi and his famous Apollo sanctuary). According to one ancient story, reported by Pausanias (10.6.2; also cf. Suda s.v. Λυκωρεύς), the city's name comes from the howling of the wolves (λύκων ὠρυγαῖς) that led the residents to the peak of the Parnassus, which saved them from Deucalion's Flood (cf. Daverio Rocchi "Lycorea." Brill’s New Pauly). The wolves were the divine messengers of the god(s).

The stories of Apollo as "wolf god" and Lykoreia also lead us to this story from the Apollo Sanctuary of Delphi recorded by Pausanias (Paus. 10.14): "Near the great altar is a bronze wolf, an offering of the Delphians themselves. They say that a fellow robbed the god of some treasure, and kept himself and the gold hidden at the place on Mount Parnassus where the forest is thickest. As he slept a wolf attacked and killed him, and every day went to the city and howled. When the people began to realize that the matter was not without the direction of heaven, they followed the beast and found the sacred gold. So to the god they dedicated a bronze wolf" (translation W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, Cambridge, Mass. 1918; also cf. Ael. NA 12,40). Here again, people saw the wolf as Apollo's divine messenger.

Also cf. Liliane Bodon, ΙΕΡΑ ΖΩΙΑ. Contribution à l'étude de la place de l'animal dans la religion grecque ancienne. Bruxelles 1978. Cf. study in J. Bremmer (ed.), Interpretations of Greek Mythology. Routledge. and many more. There is a certain problem with our Greek evidence, which we need to bear in mind, as I already alluded to earlier. First, much of the evidence comes from an urban context, with most of our ancient authors living in cities, sometimes retreating to their 'country estate'; these people have largely lost their relationship to nature. Let's take the example of Aristotle who wrote a certain 'zoological' account. Some modern scholars suggested that this might implies that people had limited knowledge of wolves and wolf behaviour prior to Aristotle's account. But this idea is of course not tenable since, firstly, Aristotle's knowledge of wolves would have primarily come from 2nd-hand accounts and literature, and, more importantly, people living in rural areas, like Arcadia, would have had a much more intimate knowledge of wolves for generations, acquired through experience and observations, and based on knowledge passed on from father to son, perhaps not dissimilar to North American Indians (see page 2 of website). Indeed, many people in the Greek and Roman world would have lost this more direct knowledge of animals, and nature in general, due to the increasing urbanisation across the Mediterranean World in the 1st millennium BC. As a result, the image of the wolf portrayed in Greek and Roman sources was changing through time; it is still rather positive in some of our earlier reports, like Homer, but certain negative views of wolves gradually become part of the general image. As a result, the story of king Lykaon might already have gone through various re-interpretations: it is clearly seen as a negative event, with wolves being 'cunning' and eating humans. - But how different was the original story, esp. in Arcadia...?

Perhaps a little excursion to the Gilgamesh epos from the 3rd millenium BC in useful here. It mentions the perhaps earliest known 'transformation' from man to wolf. This time, the hero Gilgamesh talks to the goddess Ishtar:

"(...) You have loved the shepherd [or 'goat herder'] of the flock; he made meal-cakes for you every day, he daily slaughtered a child for your sake. Yet, you struck and turned him into a wolf; now his own herd-boys chase him away, his own dogs snap his flanks" (Gilgamesh VI). The Gilgamesh epos did clearly inspire lots of Greek myths, and the goddess Ishtar influenced Astarte and Aphrodite in later times across the Mediterranean. As in the case of the Greek King Lycaeon, we see the allusion to human sacrifice here, but this seems rather unrelated to him being turned into a wolf; rather, it seem ironic that a shepherd is turned into a wolf, and it was no punishment, as in Lykaion's case, but merely Ishtar's sense of humour... Italic & Etruscan Wolf Cults // Italische und etrukische WolfsverehrungThe wolf was not only sacred in Rome (see above). We also find evidence for wolf cults in other parts of ancient Italy.

For example, among the Falsicans in the archaic period, the wolf seem to have been considered sacred. There is a ancient mythical story, narrated by Servius in his comentary on Vergil's Aeneid (writing around AD 400; Serv. Aen. 11.785), of shepherds who chased the wolves; until they arrived at a cave emanating pestilential gases that killed people standing nearby. It seems that harassing the sacred wolves was a taboo; they were told that they could calm it down by imitating wolves (lupos imitarentur). Subsequently these people were called the Hirpi Sorani, "the wolves of Soranus", the priests of the local sanctuary (hirpi is Faliscan for 'wolf'; Soranus is the local god, perhaps related to Śuri, the Etruscan god of purication and prophecies (who also had the wolf as attribute)? Are the wolf priests purifying the people? Also, this may be another possible relation to Apollo [Lykaios]?), and later association of this cult with Apollo, not Soranus. (Cf. M. Rissanen, The Hirpi Sorani and the wolf cults of Central Italy, Arctos 46 (2012) 115–35).

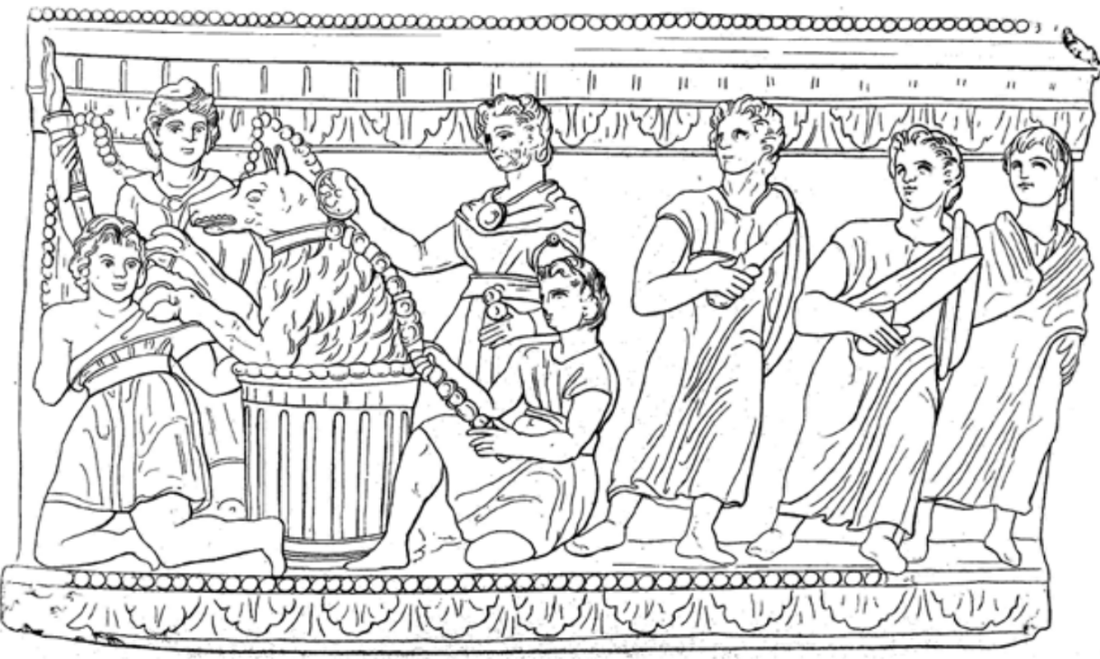

Wolves at an altar. Are they merely plundering the sacrificial meat from the altar?

This reminds us of Servius' story where wolves suddenly appeared and plundered the entrails from the altar. Here, obviously a board provides access to the altar: are they the sacred animals/gods for whom the sacrifice was intended? Etruscan black-figure amphora from c.500 BC.

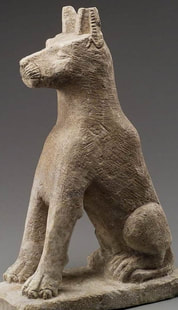

In Etruscan religion, Aplu (=Apollo), Suri (=Soranus) and Aita (=Hades) all had the wolf as attribute. Aita, for example, is shown with a wolf cap in Eturscan tomb paintings.

(Cf. E. Simon, "Gods in Harmony: The Etruscan Pantheon", in N.T. De Grummond & E. Simon (eds), The Religion of the Etruscans, Austin 2006; also cf. E.H. Richardson, "The Wolf in the West", Journal of the Walters' Art Gallery 36 (1977), 91-101; J. Elliott, "The Etruscan Wolfman in Myth and Ritual", Etruscan Studies 2 (1995), 17-31).

A 7th century BC stele discovered in an Etruscan cemetery at Marano di Castenaso (Bologna), depicting a wolf, perhaps a dog (hardly a feline - or "quasi certamente" a lion - as suggested by the Soprintendenza!), surrounded by a number of symbols (e.g., discs, swords) in Orientalizing style (see: http://www.archeobologna.beniculturali.it/bo_castenaso/marano_necropoli/scavo_07.htm)

Taboo words & wolf people

One linguistic note: one can notice over and over again that wolves are not always called wolves (and that terminology changes in many languages... the original word might get limited to a mythical context, or even tabooed, while new words develop to describe contemporary, mortal wolves). We have seen in Japan (see my second wolf mythology page) that some wolf deities/spirits were called inu, 'dog'. In Latvian, too, we find for example meya suns, "forest dog" (cf. Gamkrelidze et al. op. cit., p.415). Also see above for the ancient Celtic word cuno which describes both wolves and dogs during the Roman period.

"Wolf People": a number of ancient peoples are called after wolves. Apart from the Hirpini (from *hirpus, "wolf") (mentioned above), we also find:

Hittite Mythology / Hethitische Mythologie // le loup dan la mythologie hittite

We are still in the sphere of Indo-European religion, but moving back in time to the 2nd millenium BC and the Hittite Empire (the language is Indo-European and closely related to Germanic languages; we can therefore expect certain 'parallels'). There, wolves seem to have symbolised inter alia unity and omniscience, features that we also find in many other cultures. In our ancient sources, we find for example king Hattusilis I, in the 17th century BC, urging his warriors to unite "like a wolf pack". We also find the Hittite term LÚMES UR.BAR.RA, "wolf people" or "wolf men" (pesnes ulipnes) (referring to certain dignitiaries or funcionaries in Hittite texts). Dressing in wolf skin seems to provide magical power, among others omniscience (also see the Germanic 'wolf warriors', Old Norse: úlfheᵭnar [úlfr, "wolf"], very close to the Hittite term).

We also find the expression "You have turned into a wolf" in the Hittite Laws (§37 for the abductor of a woman) - similarly the Sanskrit "he is a wolf" for a special juridical status, or Old Icelandic "shall be called a wolf" (cf. Gamkrelidze et al., p.414; Lamb, p.63: in Old Norse morᵭvargr denoted a man outlawed for murder [vargr as synonym for úlfr, "wolf"]). There is also an allusion to a mythical capture of the wolf by myhical beings: "seize the wolf by his paws and the lion by his jaws" (Gamkrelidze et al. p.428, different translation in Lamb, pp.64f; KUB XII 63, 21-34). This may remind us of a much later coin from Tarsus, once part of the Hittite sphere of influence, depicting the god 'Apollo'(?) seizing two wolves by their front paws (see right column on this page). The Hittite story of seizing the wolf and lion relates to the house of the storm god. Unfortunately, our knowledge of the wolf in Hittite myth is extremely limited, and in iconography, the lion seems to have been more popular. But Lamb (op. cit., p.63) provides food for thought, based on a linguistic study: the Hittite term for god's creatures was siunas huidar; huidar can also denote a wolfpack as in huednas pankur (equal to ulipnas pankur, "wolf's family"). This might once again reflect a relation between wolves and creation that might have survived in an Indo-European language, even though the actual myths are lost (Lamb, p.63 also shows the linguistic parallels between the Hittite word for wolf, huidar, and the Norse god Fenrir). (For discussion and further bibliography, cf. Thomas V. Gamkrelidze, Vjaceslav V. Ivanov, Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans, a reconstruction...; Sydney M. Lamb, Sprung from some common source: Investigations into the prehistory of Languages). |

More Examples of Mythical/Divine Wolves

ITALY - GREECE - ASIA MINOR - KELTIKE - CHINA - EGYPT

'Celtic' wolves

Roman she-wolf

|

Roman Britain

Isis on Wolf

Greek & Hellenistic World

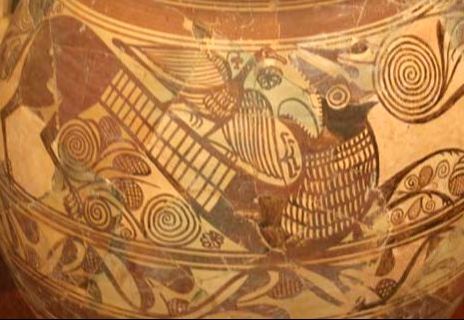

A representation of the same myth. Here we can see that we are dealing with a winged wolf, crouching to the left, looking to the right. The fish, tunny, is now 'swimming' under the wolf. The wolf as mythical, celestial deity?

(Mysia, Kyzikos. electron coin, c.500-450 BC). A representation of the same myth. Here we can see that we are dealing with a winged wolf, crouching to the left, looking to the right. The fish, tunny, is now 'swimming' under the wolf. The wolf as mythical, celestial deity?

(Mysia, Kyzikos. electron coin, c.500-450 BC).

cc

Κύζικος/Kyzikos/Cysicus was a city in Mysia (NW Turkey), traditionally said to have been founded by the Argonauts.

We might also think here of Meter Theon, the Mother of the Gods, a title given to a number of important mother goddesses in the ancient world, notably Cybele. In the Homeric Hymn 14 to the Mother of the Gods (c.7th-4th century BC) we are told that: "[Meter Theon] is well-pleased with the sound of rattles and of timbrels, with the voice of flutes and the outcry of wolves and bright-eyes lions, with echoing hills and wooded coombes" (trans. Evelyn-White). And in the Greek Lyric Anonymous Fragments 935 we can read among others "of the Mater Theon, how she went wandering through the mountains and glens trailing her flowing hair and distraught in her mind. (...) And Kypris [Aphrodite] urged her (...): ‘Mother, go off to the gods: father Zeus summons you; and do not keep on wandering over the mountains; have fierce lions or grey wolves become your friends?’" (Inscr. shrine of Asklepios, Epidaurus, (trans. Campbell, Greek Lyric V). |

Italy - Etruscans

This representation from an Etruscan urn is similar to the depiction above, only the wolf is now a "wolf man", human body with wolf head. And the humans' actions are also clearly different. Is this really a representation of the same myth as some have suggested? Is it really a "wolf" emerging from the "underworld"?

On these urns depicting a 'monster' (Olta?) coming out of a 'well', also see Chierici Armando 1994, "Porsenna e Olta, riflessioni su un mito etrusco", MEFRA 106/1, 353-402,

doi : 10.3406/mefr.1994.1851. ChinaNear East

Roman period, again...

A wolf- (or dog-)headed deity on this Roman limestone relief from the 3rd century AD, depicting some form of offering scene.

A syncretic, hybridised deity, taking up characteristics from different deities: a wolf head, crowned with sheaves of wheat, and holding a key,

the snake-like legs perhaps more an indicator of the cosmic warrior god Abraxas

(but he is usually represented

with the head of a lion or cock, together with sword and shield; also, other depictions from the Roman empire of snake-like monsters, e.g. from the Jupitergigantenreiter in Eastern Gaul); the rest of the god is human, clothed in animal skin; in his right hand, he holds a key, and in his left hand, a caduceus and sheaves of wheat (the caduceus is an attribute of Mercury, together with the ram depicted on the left), and also some 'poppies'(? - healing quality?).

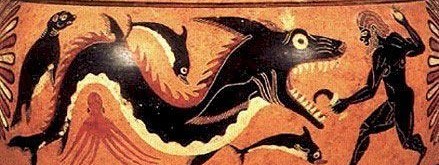

A bearded man kneeling at the right, presenting a loaf of bread on an offering table, its support with a lion head and a feline paw. (There are some Greek representations of a ketos, "sea monster", with a head resembling perhaps a wolf, notably the unique represenation of Perseus, Andromeda and Ketos on a Corinthian black-figure vase of the 6th century [coincidence? Corinth is not fa away from Arcadia...] (for vase painting, cf. Woodward, Perseus, 1937 and S.R: Wilk's Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon, p. 53).

But at the end of the day, we do not know what kind of deity we are dealing with here: wheat, key, caduceus, poppies,... - does seem to be rather benign: fertility and propserity? and the offering is also rather harmless: a load of bread. (Sorry, though thoroughly checked when auctioned at Christies, and deemed genuine, we do not seem to know where the stele was found).

|

Disclaimer: please surf at your own risk...

The information contained in this website is for general information purposes only. I endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, but I cannot guarantee its completeness, accuracy, reliability or suitability. I am not responsible for any action taken as a result of the information or advice on my website.

Through this website you are able to link to other, external websites which are not under my control; these links are being provided as a convenience and for informational purposes only; the inclusion of any links does not necessarily imply a recommendation or endorse the views expressed within them, and I bear no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.

Copyright:

The content and research of this website is protected by copyright. No portion of this website may be copied or replicated in any form without the written consent of the website owner. Many of the images on this page come from external sites: I have tried to find out the copyright owners of all the images on this page and I apologise if I missed someone or if I was not able to find the original sources/photographer/copyright owner. The site is still work-in-progress: sorry if I forgot to add a reference.

How to cite this page:

Raph Häussler (2016) Wolf & Mythology, retrieved from https://ralphhaussler.weebly.com/wolf-mythology-italy-greek-celtic-norse.html

The information contained in this website is for general information purposes only. I endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, but I cannot guarantee its completeness, accuracy, reliability or suitability. I am not responsible for any action taken as a result of the information or advice on my website.

Through this website you are able to link to other, external websites which are not under my control; these links are being provided as a convenience and for informational purposes only; the inclusion of any links does not necessarily imply a recommendation or endorse the views expressed within them, and I bear no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.

Copyright:

The content and research of this website is protected by copyright. No portion of this website may be copied or replicated in any form without the written consent of the website owner. Many of the images on this page come from external sites: I have tried to find out the copyright owners of all the images on this page and I apologise if I missed someone or if I was not able to find the original sources/photographer/copyright owner. The site is still work-in-progress: sorry if I forgot to add a reference.

How to cite this page:

Raph Häussler (2016) Wolf & Mythology, retrieved from https://ralphhaussler.weebly.com/wolf-mythology-italy-greek-celtic-norse.html